However, neural progenitors that are capable of participation in neurogenesis are present in certain regions such as the dentate gyrus of the rat, and in the subependymal of rodents. Mature neurons are unable to divide, so their destruction may lead to a neurological deficit.

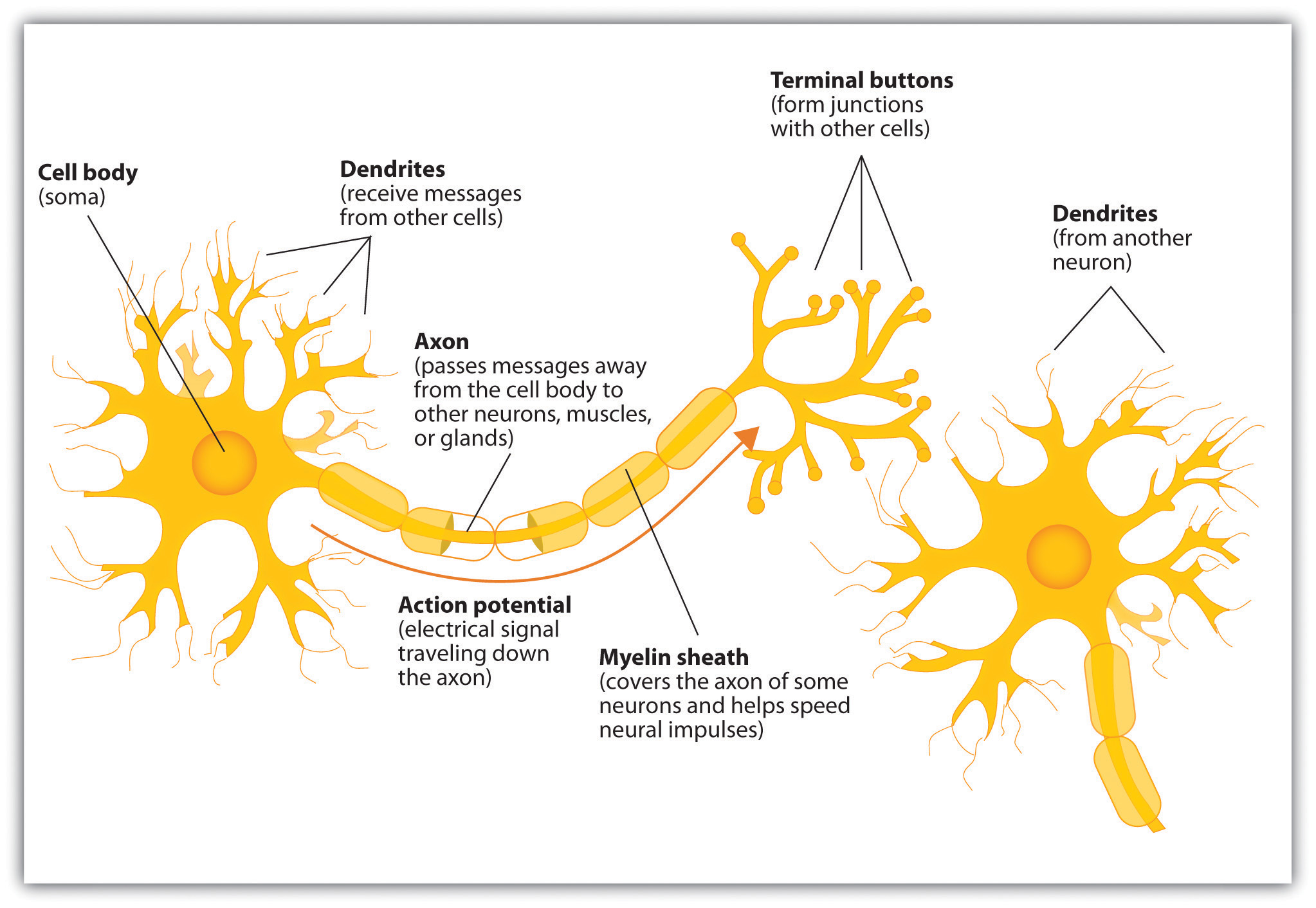

The variety of interactions among neurons enables the transmission of impulses to perpetrate diverse functions within the body. Graded potentials are also important to note as they vary in strength, and lose amplitude throughout their transmission. As a depolarizing threshold stimulus occurs, an action potential that is consistent in amplitude is generated and travels down the axon to the terminal. The resting membrane potential of typical neurons is around -70 mV. Potassium, sodium, and chloride ions are the greatest contributors to the membrane potential of the common neuron. Neurons propagate their potentials by ion movement through voltage-gated ion channels (though calcium channels are largely voltage-independent) across their membranes. Axonal transport is carried out by proteins such as kinesin and dynein. Axons typically end in an axon terminal at which neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, or neurohormones are released in the conversion of the electrical signal to a chemical signal which can cross the synapse or neuromuscular junction.

In addition to afferent signaling, dendrites can be involved in protein synthesis and independent signaling functions with other neurons. There may be one or many dendrites associated with a single neuron depending on its function and location. The soma contains the nucleus and other organelles necessary for neuronal function. Neurons exist in a variety of forms including multipolar, bipolar, pseudounipolar, and anaxonic which differ primarily in their number and arrangement of axons and dendrites. Neurons are characterized by the long processes which extend out from the cell body or soma. Neurons are unique in their ability to receive and transmit information.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)